Understandably, multinationals concentrate more on their daily operations, as it is vital to their profitability which concerns the most to their shareholders. Some companies allocate little or sometimes no resources to comply with their tax obligations unless they hear the footsteps of the tax auditors on the way to their doors. Consequently, MNEs usually gather their tax information at the last minute. This fact not only leads to the documentation of poor quality, but in the worst-case scenario, MNEs may also even miss the stipulated deadlines for their TP compliance requirements and are eventually subject to tax penalties.

So, what are the deadlines that MNEs need to be aware of when preparing their TP documentation? Based on our observations on the country-specific legislations, these deadlines can be roughly classified into several types described below. We focus on the local file requirement, as it’s the most popular (and time-consuming) format for most multinationals.

1. There is a submission deadline when the taxpayer needs to submit their documentation

Countries such as Argentina, Denmark, Mexico, Qatar, Portugal, South Korea and South Africa have stipulated that MNEs need to submit their TP documentation before or on a specific deadline. The submission deadline is often aligned with the corporate tax return. That said, there are also countries where submission deadlines differ from the timing of filing the corporate tax return. For example, in Chile, the deadline for corporate tax returns is due by the end of April but for TP documentation is by the end of June, which is instead in line with the CbC Affidavit (”DJ-1937”). Also, noteworthily, Australia by law doesn’t require MNEs to prepare and lodge the TP documentation along with the corporate tax return. Still, if they want to secure a “reasonably arguable position” during tax audits for penalty protection purposes, TP documentation remains a prerequisite.

2. There is no submission deadline, but a preparation deadline

Based on our observations, most local tax jurisdictions don’t require proactively submitting the documentation but require MNEs to prepare their local files and have them at hand. In such a case, tax authorities can request the documentation after the corporate tax return, usually during a tax audit. However, this does not mean MNEs must prepare their documentation only when they receive an official request. In most tax jurisdictions, the documentation must be prepared on a so-called “contemporaneous basis.” According to the UN’s TP manual (2021), this jargon in the TP world means “Transfer pricing documentation prepared at the time that the relevant transactions occur”. However, different tax authorities still retain their right to interpret this term at their discretion, so MNEs should comply with the local tax administrative procedures.

In principle, contemporaneous documentation should demonstrate that the transfer pricing method and its application provide the most reliable measure of an arm’s length price based on information reasonably available at the time of the transaction. In practice, at the latest, MNEs should confirm that their transfer prices align with the arm’s length nature at the time of filing the corporate tax return. That being said, usually, MNEs will have some time to present their TP documentation to the tax administration, from so-called “in a timely manner” (e.g., Vietnam) to 180 days (e.g., Thailand if it’s the first-time request). The majority of the timelines fall between 15 to 30 days. Noteworthily, some countries do not demand MNEs to submit the TP documentation but require them to confirm the existence of TP documentation by a specific date. For example, in Italy, although not required to be submitted by the date of the corporate tax return, the Master File and Local File must be signed by the legal representative or delegate of the MNEs by electronic signature with a time stamp to be affixed by the date of presentation of the corporate tax return.

3. There is no given deadline

Some tax regulations do not stipulate submission or preparation deadlines. They can be further classified into two kinds of tax jurisdictions:

- Countries where the TP documentation is implemented but is only required to be submitted upon request

In these countries, MNEs only need to submit their TP documentation when receiving an official request from the tax authorities. These countries include Bangladesh, the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Norway, Saudi Arabia, Slovakia, etc. Noticeably, TP documentation is usually required to be prepared annually and often contemporaneously. For example, in Israel, TP documentation only needs to be finalized when receiving an official request and should be submitted within 60 days. However, a locally specific TP form to declare international transactions (”Form 1385”) must be appended to the corporate tax return, due within five months after the end of the tax year. Similar forms exist in many other jurisdictions. In practice, the required information for these forms comes from a local file. Therefore it’s challenging to complete the form without having documentation available. - Countries where the explicit TP documentation requirement is still not implemented

Most of them only have regulations on MNEs to file CbC reports and/or some locally specific TP-related supplements, such as tax returns, tax forms, tax affidavits, tax declarations, TP appendixes to the corporate tax return, etc. For example, in Switzerland, as of this point, only CbC reporting is implemented by the local tax regulations. Therefore, there are no specific TP documentation requirements regarding Master File or Local File. However, as Switzerland also participates in the BEPS project and complies with the arm’s length principle, It is still considered best practice to document intercompany transactions and prepare extensive documentation for higher-risk transactions, especially in cases of receiving an official inquiry by the tax administration or seeking an advanced tax ruling.

In Summary

To sum up, there are various types of timelines that can be confusing to MNEs. They have different meanings and applications. MNEs need to pay attention to those deadlines to keep their TP compliance work neat and tidy. Based on our observations, no matter whether the domestic tax regulation requires to submit, prepare, or has no specification on TP documentation, documenting the intercompany transactions in a contemporaneous as well as ordered manner no later than the date of filing corporate tax return remains the best practice in terms of TP documentation compliance.

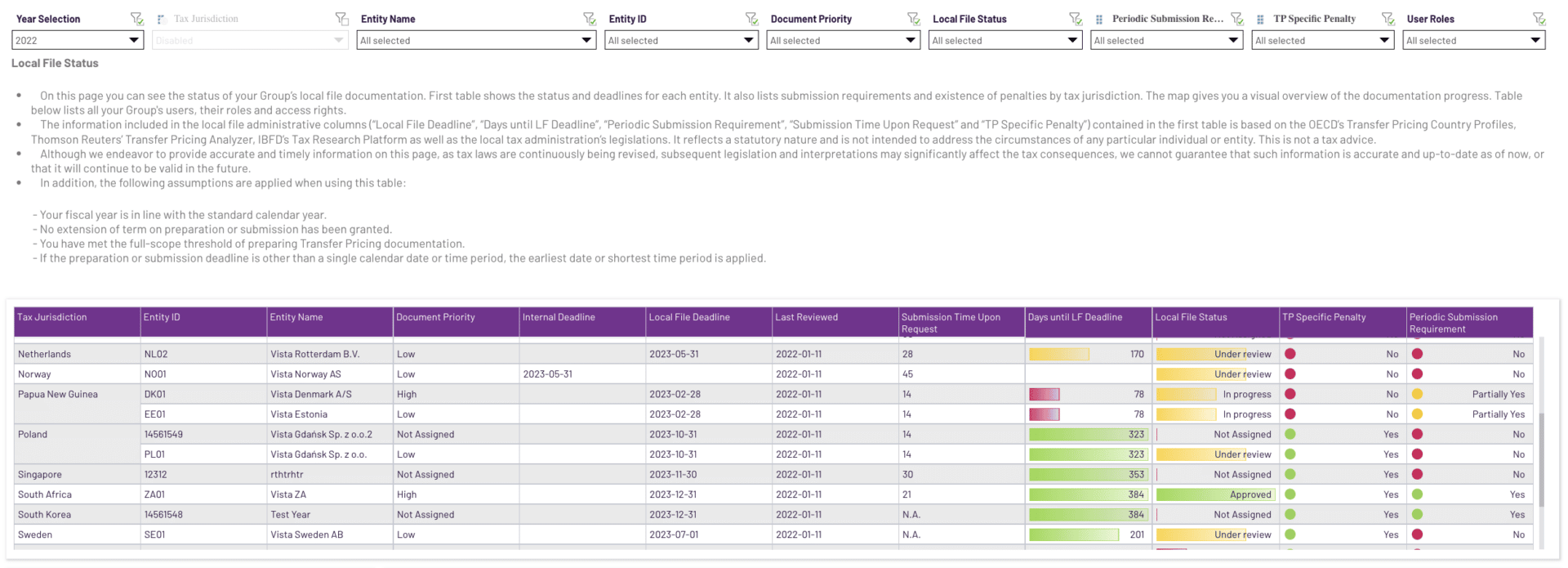

Thanks to the digital world we are immersed in, MNEs can spare themselves from manually tracking the deadlines in the tax jurisdictions where they have obligations to prepare documentation. Nor do they necessarily have to depend on external tax consultants in those jurisdictions. By utilizing a digital platform, MNEs can centralize their cross-border taxation practice in just one place, managed transparently, and cost-efficiently. For example, in Aibidia’s TP Doc application, users can have an overview of the country's administrative deadlines in which their legal entities are located. In addition, the timelines for the statuary deadlines are automatically calculated, and users can set their internal deadlines for their own project management purposes.

%20(2).png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.svg)